Sigmund Freud and the Birth of Psychoanalysis

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, was a visionary who revolutionized our understanding of the human mind and behavior. His groundbreaking theories have pierced the veil of human consciousness, illuminating the profound complexities of psychology. Freud’s work laid the foundation for modern psychotherapy, and its residual influence is seen across various fields, from literature and film to neuroscience and philosophy. This article explores the life of Sigmund Freud, the inception of psychoanalysis, and its lasting legacy.

Born on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg, Moravia (now Příbor, Czech Republic), Freud was a precocious child who showed an early passion for knowledge. He pursued medicine at the University of Vienna, which marked the beginning of his journey into the labyrinth of the mind. Freud’s medical career was initially focused on neuropathology, but his interests gradually shifted toward the psychological aspects of mental illness.

The birth of psychoanalysis can be traced back to Freud’s collaboration with physician Josef Breuer. Together, they explored the use of hypnosis and ‘talking cure’ to address the psychological ailments of their patients. One of the pivotal cases was that of Anna O., a patient of Breuer’s, who exhibited hysterical symptoms, which lessened after talking about her experiences and emotions. The case played a significant role in the formulation of Freud’s later theories about unconscious processes and psychoanalytic techniques.

Freud introduced the concept of the unconscious mind, a repository of feelings, thoughts, and memories outside of conscious awareness, which could influence behavior and personality. This was a radical departure from the prevailing notion that consciousness dictated all aspects of behavior. Furthermore, Freud posited that much of our psychological distress could be traced to unresolved conflicts residing in this unconscious domain, particularly those stemming from early childhood experiences.

One of Freud’s most influential ideas was the structure of the psyche, which he divided into three parts: the id, ego, and superego. The id represents our primal instincts and desires; the ego, our rational self that seeks to mediate between the id and reality; and the superego, our moral conscience influenced by societal norms and expectations. This model of the mind illustrated the constant tension and interplay between our innate impulses and the external world, a struggle that underlies much of human behavior.

Freud’s theory of psychosexual development also had a profound impact on psychology. He proposed that children pass through a series of stages (oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital) where the libido, or sexual energy, focuses on different erogenous zones. According to Freud, conflicts and fixations during these stages could lead to certain personality traits and psychopathologies later in life.

The method Freud developed to explore and treat the unconscious is known as psychoanalysis. An essential tool of this technique is free association, where patients are encouraged to vocalize thoughts without censorship, revealing connections and content of the unconscious mind. Through interpretation of dreams, Freud believed that he could unearth the underlying desires and conflicts disguised within the symbology of the dream world.

Another central concept of Freudian psychoanalysis is transference, the process whereby patients project feelings and attitudes from prior relationships onto the therapist. This phenomenon enables exploration of the patient’s relational patterns and helps resolve old conflicts. Countertransference, the therapist’s emotional reaction to the patient, is also explored within the psychoanalytic framework for its potential to illuminate the therapist’s biases and enhance understanding of the therapeutic relationship.

Freud’s theories, while revolutionary, have not been without criticism. Critics argue that his work was overly focused on sexuality and that his theories are not universally applicable across diverse cultures. Furthermore, some of his ideas lack empirical support, and his case study methodology has been challenged for its anecdotal nature and lack of generalizability.

Nevertheless, the legacy of Freud and his creation of psychoanalysis extends far beyond the confines of therapy. His conceptualization of the unconscious inspired artists, writers, and filmmakers to explore the depths of human motivation and symbolic representation. Freud’s ideas permeated educational practices, with educators considering childhood experiences as formative to the development of an individual’s personality and future identity. Even within the realm of neuroscience, contemporary researchers continue to investigate the complex interplay between unconscious processes and conscious awareness, an ongoing dialogue with Freud’s initial assertions about the mind.

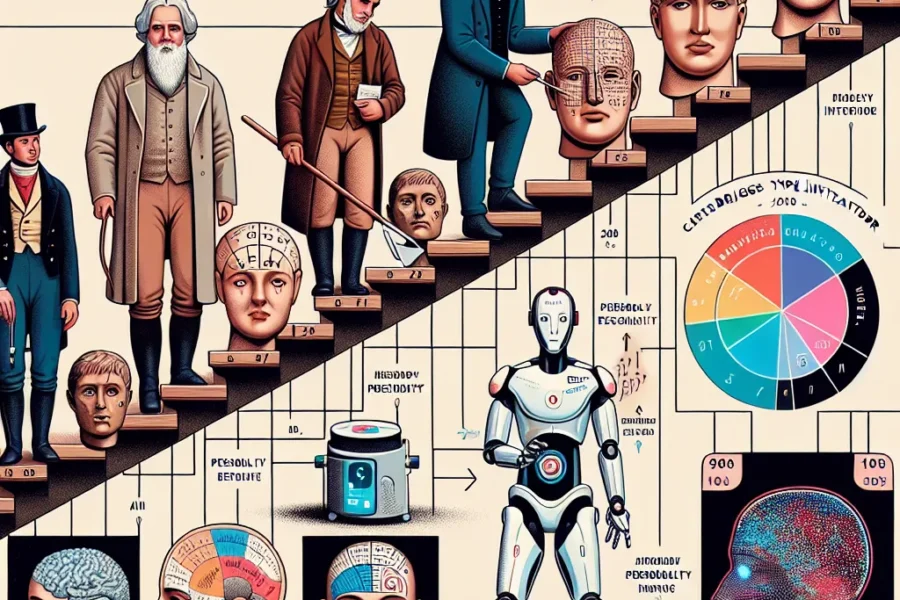

In addition to influencing the broader cultural landscape, Freud’s work has given rise to a variety of psychoanalytic schools of thought. Neo-Freudians such as Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, and Karen Horney expanded upon and diverged from Freud’s theories, developing their own psychological frameworks. Contemporary psychoanalysis has evolved to incorporate relational and intersubjective approaches, emphasizing the mutual influence and co-construction of experience within the therapeutic relationship.

One of psychoanalysis’ most enduring contributions to psychology is its insight into defense mechanisms, psychological strategies the ego employs to protect itself from anxiety and conflict. Concepts such as repression, denial, projection, and sublimation are now part of the common lexicon, revealing the subtleties of human self-deception and coping.

Freud’s influence on therapeutic practice is equally significant. The introspective focus of psychoanalysis paved the way for various forms of talk therapy and has been integrated into modern therapeutic techniques like psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). While these contemporary modalities may differ from traditional Freudian psychoanalysis, they often share the emphasis on exploring the psychological roots of emotional distress.

To this day, the impact of Sigmund Freud and the birth of psychoanalysis are felt across various facets of human endeavor. By opening the door to the uncharted territory of the unconscious, Freud provided a language and framework that have allowed countless individuals to better understand themselves and the complex tapestry of the human condition. Whether through the lens of critical scrutiny or devoted application, his legacy continues to illuminate the mysterious inner workings of the mind.

The nuanced exploration of the psyche initiated by Freud has laid the foundation for an ever-expanding conversation about what it means to be human. Despite the advances in modern psychology, the essence of psychoanalysis—its focus on the dialogue between the hidden and the known, the past and the present, and the irrational and the rational—remains a testament to Freud’s extraordinary vision. The birth of psychoanalysis not only sparked an intellectual revolution but also provided a path to deeper self-awareness and healing for generations to come.

In examining Freud’s legacy, we can see that while the field of psychology continues to evolve, with new theories and methods emerging, the pioneering work of Sigmund Freud remains central to our understanding of human nature. His contributions outline the contours of a dynamic mental landscape, a legacy that spurs ongoing discourse, research, and discovery. Quite simply, the birth of psychoanalysis at the hands of Sigmund Freud marks one of the most significant milestones in the history of psychology, a beacon that continues to guide and influence our quest to comprehend the complexities of the human mind.

Leave a Comment