John B. Watson: A Pioneer in Behavioral Psychology

Modern psychology is a field enriched by numerous theories, research studies, and groundbreaking discoveries. Among the pioneers who influenced the course and development of psychology, John Broadus Watson holds a distinguished place. Known as the father of behaviorism, Watson revolutionized psychology by introducing a new school of thought focused on observable behavior, rather than on introspection and the unconscious mind. In this discussion, we delve into the life and work of John B. Watson, a brilliant mind that helped shape behavioral psychology into a science focused on measurable outcomes.

Born on January 9, 1878, in Travelers Rest, South Carolina, John B. Watson came from a relatively modest background. Despite early struggles, he demonstrated extraordinary intellectual abilities, which led him to Furman University where he earned his master’s degree at the age of 21. Watson continued his academic pursuits at the University of Chicago, where he was heavily influenced by functionalist psychology and studied under the guidance of pioneering psychologist James Rowland Angell. In 1903, Watson earned his Ph.D. in psychology and began his prolific career, shaping the field of behavioral psychology.

Behaviorism, the theory that Watson championed, was grounded in the belief that psychology should concern itself with the observable behavior of individuals, instead of their unobservable internal thoughts and emotions. He argued that behavior could be studied in a systematic and observable manner, independent of subjective mental states. Watson’s scientific approach to psychology was a stark contrast to the introspective methods that dominated the field at the time.

One of Watson’s most significant contributions to psychology was his publication of the article “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views it” in 1913, which is often regarded as the behaviorist manifesto. In it, Watson outlined the principles of behaviorism and called for a radical reformation of psychology. He believed that behaviorism could make psychology as objective and standardized as other natural sciences, like biology and chemistry. Watson’s manifesto was monumental in the shift towards behavioral research in psychology.

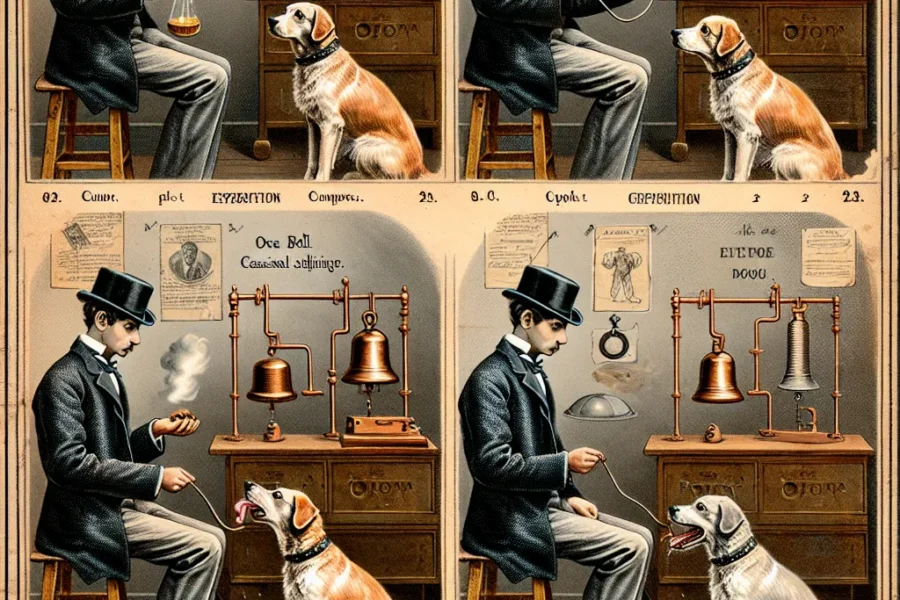

Throughout his career, Watson conducted several notable experiments that emphasized the importance of nurture over nature in the development of individuals. The most famous of these was the Little Albert experiment, which he carried out with his graduate student Rosalie Rayner in 1920. In this controversial study, Watson and Rayner demonstrated that they could condition a young child, referred to as Little Albert, to fear a white rat—a fear which could be generalized to other white, furry objects. This experiment supported the idea that emotional responses could be learned through classical conditioning and provided evidence of the environment’s strong influence on behavior.

Watson’s research in the realm of child rearing and development further reinforced his belief in the role of the environment. His book “Behaviorism” (1924), and later, “Psychological Care of Infant and Child” (1928), outlined his thoughts on child development and parenting, in which he argued that children should be treated as young adults and parents should foster their independence from a young age. His views on child-rearing, some of which are regarded as extremely rigid and emotionally detached by current standards, spurred much debate and laid the groundwork for later developmental theories.

Watson’s contributions to the advertising industry are an often-overlooked part of his legacy, yet they showcase the practical application of psychological concepts to daily life. After his academic career came to an abrupt end because of personal controversies, Watson transitioned to working in advertising. He applied his understanding of human behavior to effectively market products, utilizing emotions and behaviorist principles. Watson’s advertising work further illuminated how behaviorism could be not just a theoretical viewpoint, but a functional tool in influencing public behavior.

His impact on psychology is indelibly tied to behaviorism’s eventual evolution into further theoretical frameworks, like cognitive behaviorism, which combines both behavioral and cognitive theories, and behavior analysis, an approach still widely used today in therapeutic settings and education. Moreover, Watson’s ideas paved the way for notable psychologists who built upon his concepts, such as B.F. Skinner, who expanded the theory of behaviorism to include operant conditioning. This succession of thought emphasizes Watson’s role in creating a foundation from which much of contemporary psychological practice derives.

Throughout his career, Watson faced both staunch opposition and great acclaim. Traditionalists in the field of psychology were critical of his denunciation of introspection and his dismissal of the conscious and unconscious mind as topics worthy of scientific study. However, Watson remained steadfast in his approach, confident that behaviorism provided a clear, observable, and quantifiable method for the study of psychology. His commitment to a scientific methodology in psychology opened the door to empirical research and experimental methods that are considered standards in the field today.

Beyond academia, the legacy of John B. Watson endures in the way we understand human learning, personality development, and social interaction. Behaviorism’s influence percolates through educational strategies, therapies for disorders, and our general comprehension of human adaptability and change. The principle that behavior can be shaped, modified, and controlled has found applications as diverse as animal training, workplace management, and in the design of user experiences in technology.

Although Watson’s personal life, including his marital affairs and his contentious child-rearing recommendations, often cloud his image, there is no denying his profound influence on psychology. At times, he was a polarizing figure; his relentless push for a factual basis for psychological studies, however, undoubtedly shifted the field’s trajectories toward a more empirical nature. Recognized as one of the first to take a strong stand on the possibilities of environmental influence over hereditary factors in human psychological development, Watson challenged existing notions and opened a dialogue that continues to evolve to this day.

As we acknowledge John B. Watson’s enduring contributions to behavioral psychology, it becomes evident that his work was instrumental in molding an aspect of psychology that champions observable evidence over theoretical speculation. At the core of Watson’s philosophy was the conviction that through the observation of behavior, psychology could indeed become a science as disciplined as any other. His insistence on reproducibility, rigorous methodology, and objective analysis has left an indelible mark on psychological research and practice.

John B. Watson’s pioneering efforts undoubtedly shaped behavioral psychology into a science of observable human behavior. His commitment to applying scientific methods to the study of human actions has made him a pivotal figure in the annals of psychology. Despite the controversies and criticisms, Watson’s influence on the psychological landscape remains undeniable, and his works continue to inform and guide contemporary psychological thought and practice. As we examine the complex tapestry of human behavior, John B. Watson’s legacy resounds with a clear message: to understand the human condition, one must study what is seen, not just what is thought.

Leave a Comment