Pavlov’s experiments, a classical nod in the realm of psychology and behaviorism, shed light on how organisms learn from their environment. The 20th-century Russian physiologist, Ivan Pavlov, was at the forefront of exploring the associative learning processes, leading to the discovery of what is now known as “classical conditioning.” His pioneering work has since carved out a foundational niche in psychological education, fostered advances in behavioral therapy, and contributed to our understanding of human and animal psychology.

The genesis of Pavlov’s experiments sprouted from his research on the digestive system of dogs. Initially intrigued by the physiological process of digestion, Pavlov observed that dogs salivated not only in response to food but also to seemingly unrelated stimuli, such as the lab assistant’s footsteps. This observance set the stage for a series of methodical experiments that would encapsulate the essence of conditioned responses.

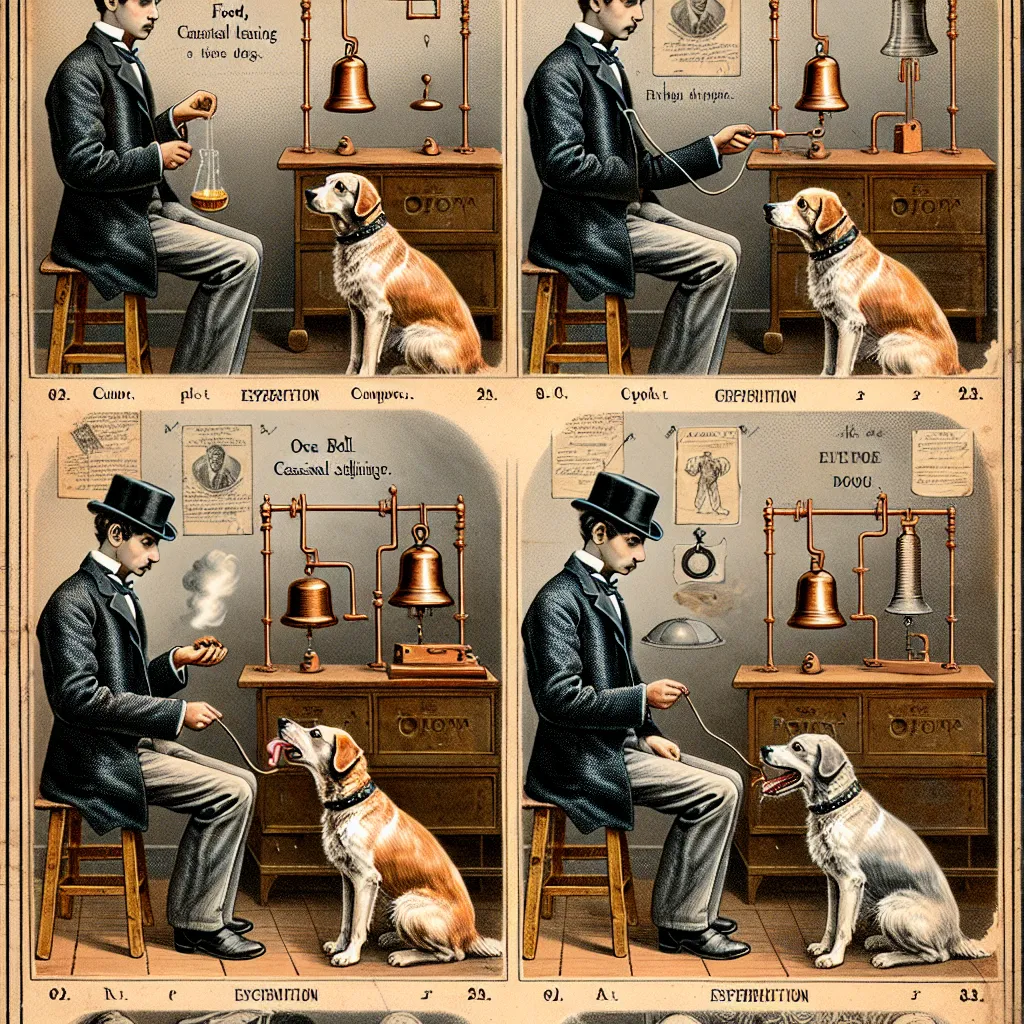

The cornerstone of his paradigm-shifting discovery was the classical conditioning experiment. In this setup, Pavlov paired a neutral stimulus, a bell, with an unconditioned stimulus, food, which naturally elicited an unconditioned response, salivation. Over multiple pairings, the previously neutral stimulus began to evoke a conditioned response, salivation, even in the absence of food. Pavlov had thus uncovered the principle that physiological reactions could be triggered by learned stimuli—a discovery that transcended the laboratory and infiltrated the precincts of psychological theory and practice.

The implications of Pavlov’s experiments were manifold, marking an era of empirical studies and application-based treatments in psychology. His findings debunked the then-dominant notion that all behavior was inherently reflexive or instinctual. Instead, Pavlov’s work posited that a significant portion of an organism’s behavior could be acquired through experience, specifically through the association between different stimuli.

Pavlov’s research played a foundational role in the development of the behaviorist movement. Behaviorism, as advocated by prominent figures such as John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner, revolved around the premise that all behaviors are acquired through conditioning. Behaviorists contended that by systematically manipulating environmental stimuli, it was possible to shape behavior. This principle resonated through decades of psychological treatments, influencing therapies for phobias, anxiety, and other behavior-related conditions.

One of the most significant impacts of Pavlov’s experiments was the inception of exposure therapy, a treatment modality for anxiety disorders. By gradually exposing individuals to the feared object or context without any danger, therapists aimed to unlearn the anxiety response—a direct application of the principles of classical conditioning. This methodology has proved to be a powerful tool in treating conditions such as phobias, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The educational implications of Pavlov’s work were equally profound. His experiments highlighted the importance of stimulus-response associations in learning processes. This knowledge steered educational psychologists to devise strategies and classroom environments conducive to learning. Reinforcement schedules and conditioned reinforcements became central teaching tools that educators employed to encourage desired behaviors and academic outcomes in students.

Moreover, Pavlov’s findings crossed disciplinary boundaries, influencing areas like marketing and consumer behavior. The concept of associating products with positive emotions or statuses, termed “classical conditioning in advertising,” has been extensively utilized to shape consumer attitudes and buying patterns. Advertisers skillfully pair products with attractive stimuli to elicit favorable, conditioned responses among potential buyers—a tactic rooted in the foundational work of Pavlov’s experiments.

Despite the pervasive influence of Pavlov’s classical conditioning, his work has also spurred critical evaluation and further research. For instance, the notion of conditioning could not wholly explain complex human behaviors, which led to the rise of cognitive psychology. Cognitive psychologists posited that mental processes, beliefs, and interpretations play a critical role in the learning process. This recognition has helped develop cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which combines the principles of behaviorism with cognitive psychology to treat a range of psychological disorders.

The significance of Pavlov’s experiments stretches even into the realm of neuroscience. Pavlovian conditioning has created avenues for exploring how different brain structures and neural pathways are involved in learning and memory. Cutting-edge research in neural plasticity and the neurobiological underpinnings of conditioning pays homage to Pavlov’s early work.

In retrospect, the simplicity of Pavlov’s experiments belies their enduring impact on the field of psychology. Pavlov’s meticulous observations and experimental rigor have set a benchmark for psychologists, urging the scientific community to adopt empirical methodologies in the exploration of the mind. His legacy is reflected not only in textbooks and therapy clinics but also in the way we understand ourselves as learning, adapting organisms.

In conclusion, the significance and reach of Pavlov’s experiments cannot be overstated. They lie at the heart of countless psychological theories and therapeutic practices that shape our understanding of human behavior and mental health today. From the conditioned responses of a salivating dog to the nuanced strategies employed in modern psychotherapy, the ripples of Pavlov’s work permeate through the waters of psychology, continually influencing and being redefined with each new discovery. As psychological science forges ahead, the concepts unearthed by Pavlov remain as relevant as ever, reminding us of the fundamental connections between our environment, our learning experiences, and our behavior.

Leave a Comment